Freud, however, later moved away from the original emphasis on the role of violent abuse in childhood, foregrounding instead Oedipal fantasies as the main causes for what was diagnosed as hysteria and neurosis, a shift that continues to fuel discussions ( van der Kolk et al. Most influential was the work in the emerging fields of neurology and psychiatry at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris by Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet, as well as the beginnings of psychoanalysis developed by Sigmund Freud, Josef Breuer, Sándor Ferenczi, and others. Modern trauma research begins at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century with the understanding that mental distress, at that time mostly diagnosed as hysteria or neurosis, can often be traced back to previous traumatic experiences. It can only be made from the experience into which it leads. The definition of an event as having a traumatic effect is always retrospective. It is not the event that is the pivotal point, but the way in which it is experienced and processed. From the angle of psychotherapy, Zepf (2001: 346) states: From the very different reactions displayed by three siblings exposed to the same regime of domestic neglect and abuse, he concludes that the social environment does not have a direct and static impact but is mediated by emotional experience ( perezhivanie), the way it is lived through, interpreted, and processed on the basis of social, personal, and situational resources (today often termed as potential for resilience). There is broad consensus on the view that different people experience potentially traumatizing events differently and do not cope with them in the same way, a fact that Vygotsky (1934/1994) recognized. It changes not only how we think and what we think about, but also our very capacity to think. Trauma results in a fundamental reorganization of the way mind and brain manage perceptions.

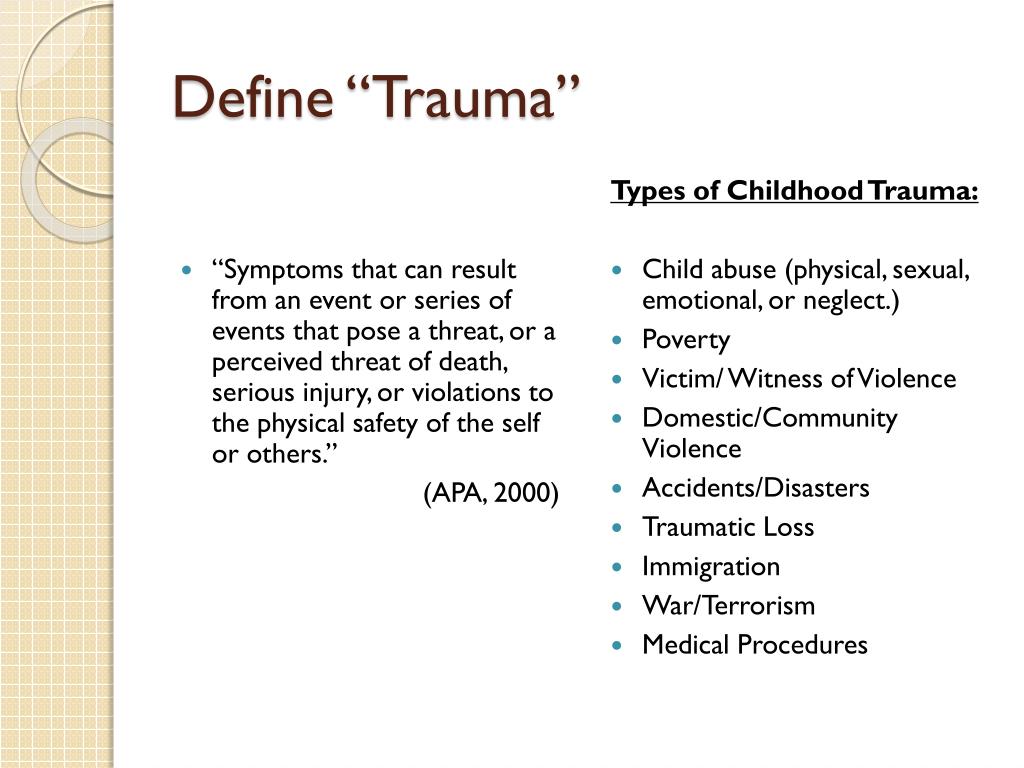

This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present. We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body. Van der Kolk (2014: 21) stresses the enduring changes brought about by the experience of trauma: … as a vital experience of discrepancy between threatening situation factors and individual coping possibilities, which is accompanied by feelings of helplessness and defenseless abandonment and thus causes an ongoing disruption of one’s understanding of the self and the world. Fischer and Riedesser (1998: 84) define trauma In specialized literature, trauma is conceived more narrowly, albeit not quite uniformly. While the term trauma was originally largely confined to medicine and psychotherapy, it has recently found its way into everyday language, where it is often used, semantically overstretched, for any form of painful or frustrating experience. THE EMERGENCE OF TRAUMA AS A MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD Throughout, we comment on the way in which linguistic analysis is deployed in the various papers in the volume to illuminate these perspectives. This will lead us to the question of what applied linguistics and in particular discourse studies can contribute to trauma research and therapy and in what ways applied linguistics can benefit from venturing into the field of trauma research. We begin our introduction with a discussion of the history of the emergence of trauma as a multidisciplinary field and go on to consider the theme of language and trauma from three perspectives: the role of language in the discursive construction of trauma as an object of knowledge, its involvement in the actual experience of trauma, and its potential and limitations in the narration of trauma. This issue presents work in applied linguistics which uses the tools of linguistic analysis to address the question of language in the experience of, recounting of, and possible recovery from psychological trauma, in personal, literary, and institutional contexts. And it seeks, on the other hand, to explore to what extent engaging with trauma can contribute to a better understanding of what Coupland and Coupland (1997: 117) called ‘discourses of the unsayable’. This special issue is, on the one hand, intended to demonstrate how linguistics may play a role as one of several approaches to the study of trauma, described by Luckhurst (2008: 214) as ‘a complex knot that binds together multiple strands of knowledge and which can be best understood through plural, multi-disciplinary perspectives’. WHY A SPECIAL ISSUE OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS ON LANGUAGE AND TRAUMA?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)